Simulation Sickness: a kinetic installation produced after a residency with the Canadian Army Simulation Centre as part of the Canadian Forces Artist Program, 2024–2025.

Shells, kites, target gongs—these are all casualties of simulated conflict. In Simulation Sickness, the stand-ins of small arms training appear as players in a security theatre. A shooting gong reappropriates its musical double meaning, reverberating with tactile transducers borrowed from vehicle simulators. Safety-orange flutes drone alongside, their colouring recalling the practice rifles that point bright muzzles at on-screen silhouettes. And a throbbing turtle shell alludes to the endangered animals that make their homes on the artillery ranges of several Eastern Canadian military bases. These landscapes, off-limits to people yet scarred by indirect fire, have paradoxically become conservation zones where wood turtles and other at-risk species survive amid the debris of spent shells, eking out a life in the blurred overlap of the real and the simulated.

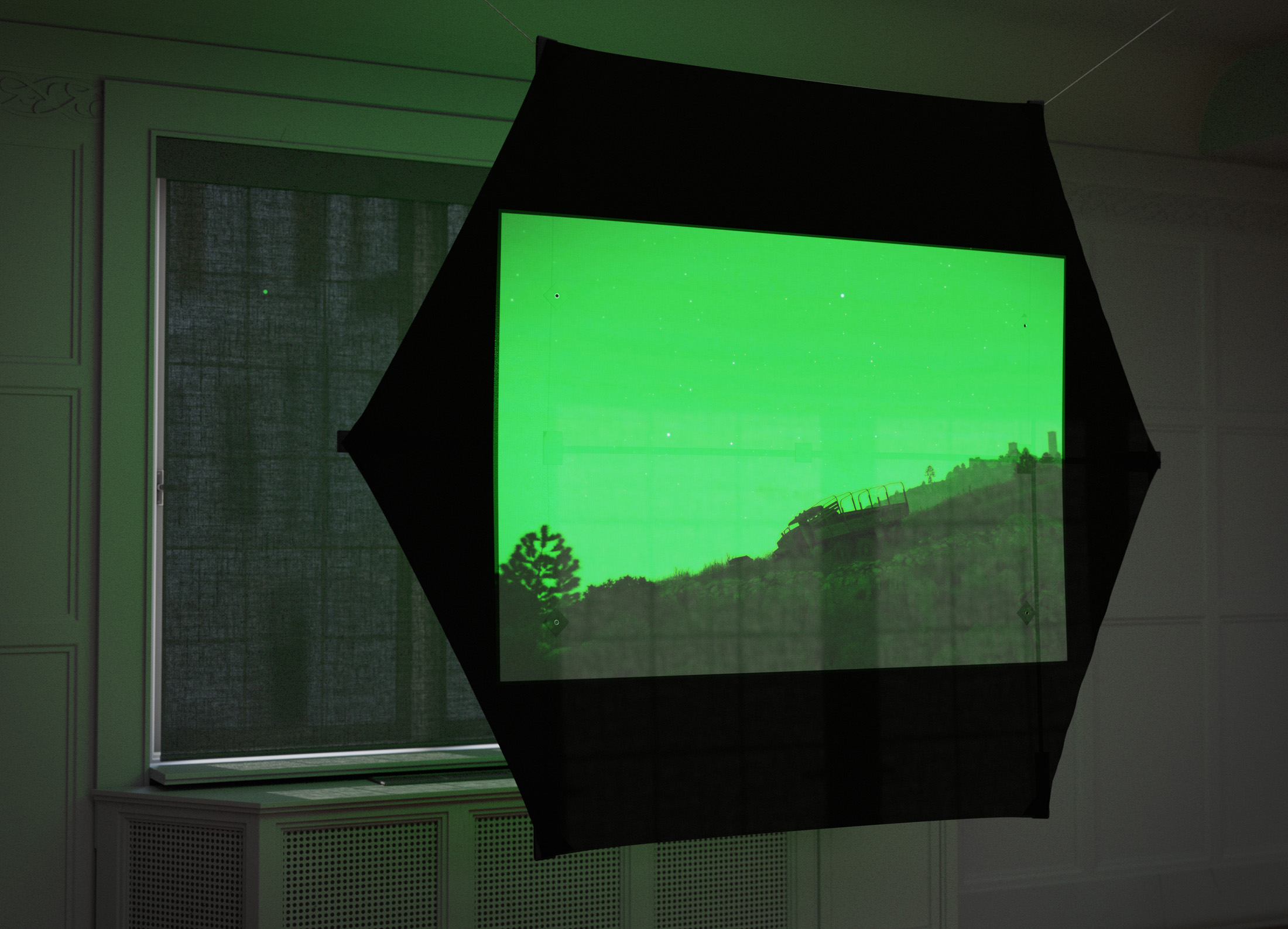

At the centre, a ticking slide projector keeps time as a virtual sun rises and falls within a military simulation software environment. Its image is cast upon a fighting kite, a precursor to the aerial surveillance of modern drones, as well as the practice target of ground-to-air combat exercises. Around it stand silhouetted figures, echoing the cut-outs of shooting ranges. But here their roles are reversed: no longer passive targets, now they perform as a musical trio. The projected slides offer discontiguous slices, strobing glimpses of a world inhabited by these ghostly surrogates. Although training environments are designed to dehumanize or even efface the opponent, this audiovisual installation stages a counter-simulation, where the abstractions of military design are unsettled by resonance, rhythm, and breath. In the suspended animation of the milsim, as in the drone’s harmonics, there is no movement but tension and release.