When the drone cuts, Wil Aballe Art Projects, Vancouver, Canada, November 11–December 23, 2023. PDF here. Rhys Edwards wrote about the show for C Magazine.

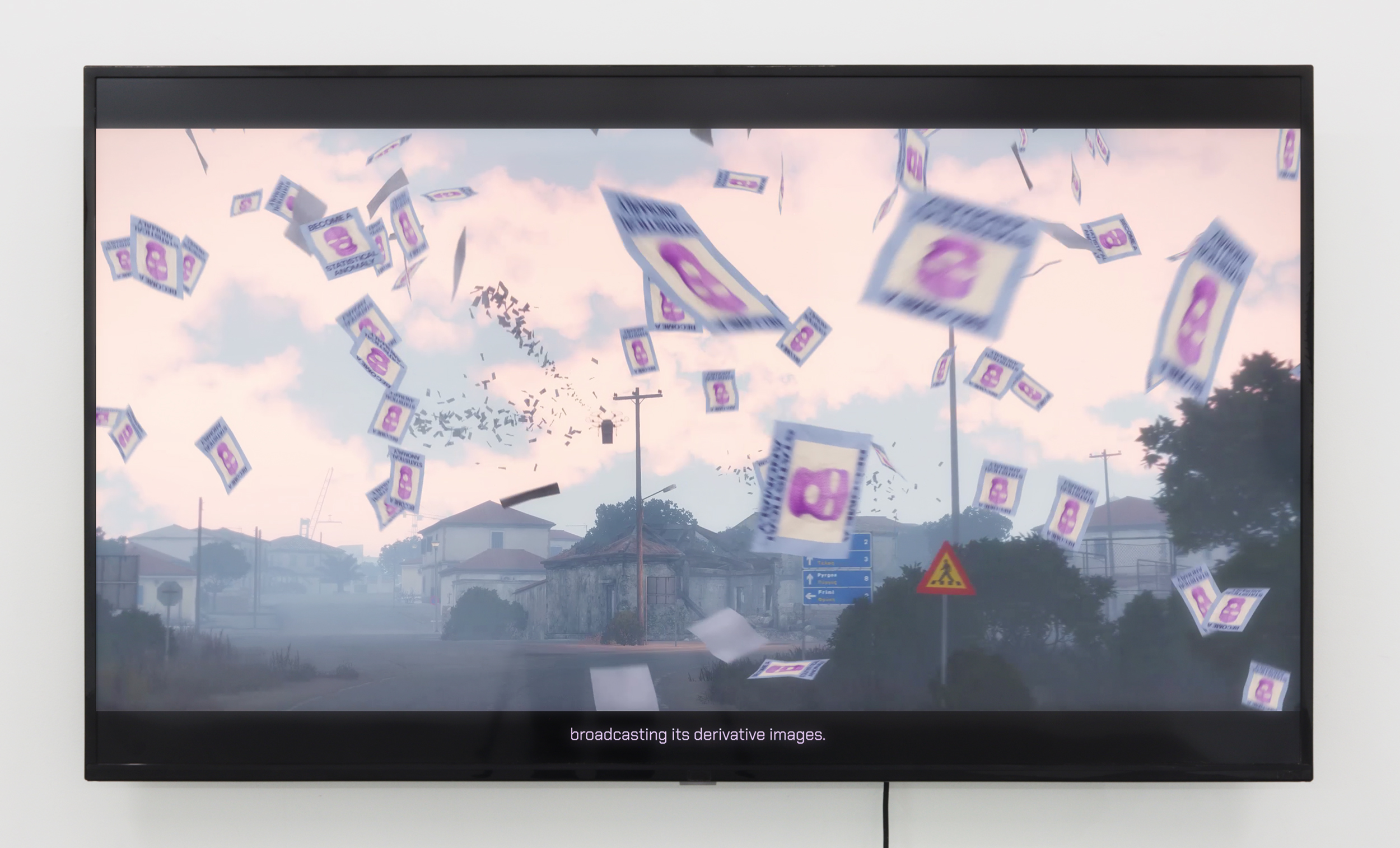

In a time of war, we bear witness to the unfolding crises of widespread displacement, devastating casualties, and environmental degradation. A flood of images, both authentic and propagandistic, captures imperialistic triumphs and defeats in equal measure. However, upon closer inspection, it becomes evident that not all of these images truthfully depict military operations in the Donbas or Panjshir; instead, some imagery is derived from screen-recordings of the military simulation (milsim) software, ArmA 3.

ArmA is a photoreal virtual environment widely used by law enforcement training programs, private military companies, and enthusiast wargamers. While much of this simulated game footage remains confined to social media feeds, select clips have erroneously made their way into national news channels. This phenomenon has persisted since ArmA 3’s public release in 2013, recurrently accompanying news reports on conflicts in Afghanistan, Pakistan, Palestine, Syria, and Ukraine.

Despite ArmA 3’s highly realistic portrayal of military tactics and even post-conflict reconstruction procedures, the milsim is troublingly devoid of women. As neither combatants nor civilians, the game contains zero female representations. Developers and users have justified this absence in various ways, citing technical limitations or the perceived irrelevance of gendered (non-male) avatars within a first-person shooter environment. Even the sequel, now in open beta, features exclusively male meshes and animations.

Amidst this tension between the game’s photorealistic graphics and its unrealistic representation of wartime gender roles, the short film As far as the drone can see makes use of open source mods to insert a female journalist into ArmA. Embedded alongside a genderfluid guerrilla cell, the film charts their covert insurrection as they interrogate the ability of a simulator to depict conflict without accounting for gender and power hierarchies.

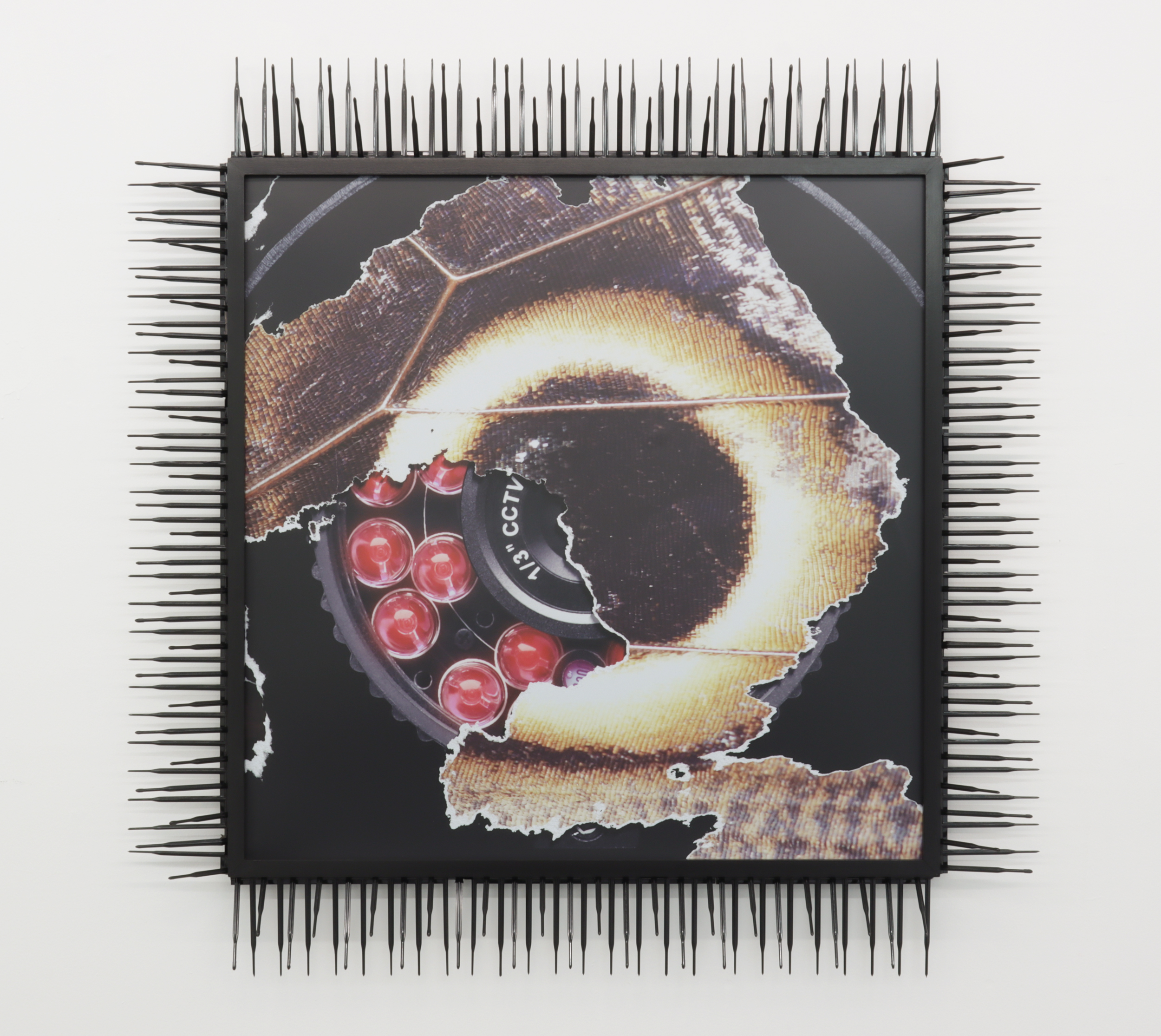

As an exhibition, When the drone cuts both extracts from and inserts into the environment of ArmA, delineating the ways in which the milsim coincides with and departs from the world it purports to represent. The virtual ruins of ArmA are materialized within the gallery space, taking the form of textiles adorned with urban camouflage mimicking the desolate construction sites, rubble heaps of redevelopment, and barbed wire fences of the gallery’s East Hastings neighbourhood. However, in the context of Vancouver, the ruins are not intended to signify destruction, but revitalization. By bringing these ambient patterns to the fore, When the drone cuts attends to the latent environmental systems that shape our perception of value.

Throughout the exhibition, the drone is deployed as a multivalent figure, redolent of both a distant observer as well as an omnipresent background hum indexing industrial activity. Within the context of ArmA, the drone (literally, an Unmanned Aerial Vehicle) becomes a way of shedding the ubiquitous male avatar. Finally, the drone manifests as a ruminative song, a suspended note meditating upon a picture of the world inseparable from its mediation.

ArmA is a photoreal virtual environment widely used by law enforcement training programs, private military companies, and enthusiast wargamers. While much of this simulated game footage remains confined to social media feeds, select clips have erroneously made their way into national news channels. This phenomenon has persisted since ArmA 3’s public release in 2013, recurrently accompanying news reports on conflicts in Afghanistan, Pakistan, Palestine, Syria, and Ukraine.

Despite ArmA 3’s highly realistic portrayal of military tactics and even post-conflict reconstruction procedures, the milsim is troublingly devoid of women. As neither combatants nor civilians, the game contains zero female representations. Developers and users have justified this absence in various ways, citing technical limitations or the perceived irrelevance of gendered (non-male) avatars within a first-person shooter environment. Even the sequel, now in open beta, features exclusively male meshes and animations.

Amidst this tension between the game’s photorealistic graphics and its unrealistic representation of wartime gender roles, the short film As far as the drone can see makes use of open source mods to insert a female journalist into ArmA. Embedded alongside a genderfluid guerrilla cell, the film charts their covert insurrection as they interrogate the ability of a simulator to depict conflict without accounting for gender and power hierarchies.

As an exhibition, When the drone cuts both extracts from and inserts into the environment of ArmA, delineating the ways in which the milsim coincides with and departs from the world it purports to represent. The virtual ruins of ArmA are materialized within the gallery space, taking the form of textiles adorned with urban camouflage mimicking the desolate construction sites, rubble heaps of redevelopment, and barbed wire fences of the gallery’s East Hastings neighbourhood. However, in the context of Vancouver, the ruins are not intended to signify destruction, but revitalization. By bringing these ambient patterns to the fore, When the drone cuts attends to the latent environmental systems that shape our perception of value.

Throughout the exhibition, the drone is deployed as a multivalent figure, redolent of both a distant observer as well as an omnipresent background hum indexing industrial activity. Within the context of ArmA, the drone (literally, an Unmanned Aerial Vehicle) becomes a way of shedding the ubiquitous male avatar. Finally, the drone manifests as a ruminative song, a suspended note meditating upon a picture of the world inseparable from its mediation.